- Home

- Aaron French

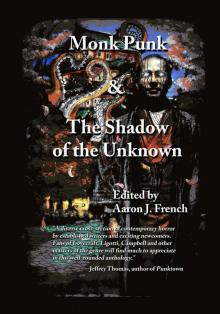

Monk Punk and Shadow of the Unknown Omnibus Page 2

Monk Punk and Shadow of the Unknown Omnibus Read online

Page 2

***

For all of their novelties and creative infidelities against the Laws of the (Narrative) Father, most punk derivatives are limited to specific temporal domains, and given their reliance on high-tech, most are plugged into the apparatus of science fiction. Monkpunk demonstrates a marked fluidity, penetrating the boundaries of genre and time—and engaging the modalities of multiple genres and timescapes—with greater ease, if only by way of a reliance not on technology but on the figure of the monk itself.

Remember: religion predates high electric technologies by millennia.

This is not to say that sci-fi monkpunk isn’t among the subgenre’s best. Or, for that matter, science fiction’s best. Bear in mind the “pulp” monasticism of Walter Miller Jr.’s A Canticle for Liebowitz (1960) and Frank Herbert’s Dune saga (1965-87). These proto-monkpunk texts continue to command vast readerships within and outside of the genre.

The monk has a longstanding rapport in the horror genre, too, H.P. Lovecraft being a seminal player and influence on the stories in this anthology, although my personal touchstone is Umberto Eco’s historical murder mystery The Name of the Rose (1980), which starkly brings into play the discourses of literary theory and medieval studies as well.

We see analogous conflations in popular fiction, spanning the literary—Neal Stephenson’s Anathem (2008)—to the decidedly non-literary—Dan Brown’s Angels and Demons (2000).

Given the default religio-spiritual identity of the monk, for better and for worse, monkpunk perhaps locates its most fertile terrain in fantasy. As the editor of this anthology, A. J. French, has told me, nearly all genre fantasy centers on European mythology, dating back to the works of J. R. R. Tolkien, C. S. Lewis, and others, accomplishing a polarized crescendo most significantly in Geoff Ryman’s recent short story “The Last Ten Years in the Life of Hero Kai” (2005). For French, Ryman institutes a new breed of fantasy, one based on a system of Eastern mythology, more Zen and Chan Buddhist than Christian.

In terms of the body, figuratively and literally, Western spirituality concerns the external, the God beyond the flesh, and before and after the flesh, whereas Eastern spirituality foregrounds, so to speak, the ghost in the machine. The stories in this anthology, the first to collect and quantify a body of monkpunk, showcase literature that runs this religious gamut. They do so while remaining faithful to their punk origins, subverting predictable notions of characterization and narrative.

***

Just as yin is intimately connected to yang, despite their binary opposition—because of that opposition—so is monk to punk.

One retains; the other pushes.

Nonetheless monks and punks possess notable similarities. Both withdraw from society into their own sect. Both deny themselves the finer things and stand opposed to capitalist subjectivity. Both uphold a code of mental ideology, a strict sense of what they believe is “them” and what they believe is “not them.”

***

Monkpunks operate on the premise of a vibrant dualism.

Monkpunks cultivate their magic, their horror, their technology in order to obtain balance and mediation. The process begins with the mind, then manifests in objective reality.

Monkpunks follow a winding path.

Monkpunks battle against enemies that lie within. Within themselves. Within the Other.

Monkpunks obtain enlightenment. Monkpunks fall like angels.

Monkpunks usher us into the human and vanish into the landscape.

***

Benchmark cyberpunk invariably depicted gritty dystopias, technologically vitalized but damaged futures in which humans have been physically and psychologically scarred and reconstructed by a wide array of technocapitalist forces. In these narratives, there is little hope; agency is a code that defies being cracked. The same might be said for most punk derivatives.

Monkpunk certainly has a palpable dark side, and it is by no means utopian. As the stories herein indicate, however, it aspires for a more optimistic view of the human condition and the powers that make (and remake) us. Above all, monkpunk is about finding equilibrium—between West and East, between good and evil, between mind and body, between the inside and the outside, between the old and the new...

And yet, like its predecessors, monkpunk stems from an aesthetic of play. With genre. With form. Ultimately with ideas.

The melodic assonance and alliteration of the term itself sets the stage for the waxing of its execution.

Monkpunk.

Bibliography:

Hantke, Steffen. “Difference Engines and Other Infernal Devices: History According to Steampunk.” Extrapolation 40.3 (Fall 1999): 244-54.

Remy, J. E. “All Sorts of Punk.” DieWachen.com. Web.

Sterling, Bruce, ed. Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology. New York: Ace Books, 1988.

Tucker, Ken. “A Splatterpunk Trend, And Welcome to It.” The New York Times 24 Mar. 1991: BR13.

About the author: D. Harlan Wilson is a novelist, short story writer, literary critic & English prof. His books include THE SCIKUNGFI TRILOGY, PECKINPAH, TECHNOLOGIZED DESIRE, THEY HAD GOAT HEADS, BLANKETY BLANK, PSEUDO-CITY & others.

Fistful of Tengu

David J. West

A monk with several weeks’ worth of beard walked into the village of Baiken. He bore only a short walking staff and the sun bleached robe on his back. His once black hair now looked frosted with the gray of age. He paused at the crossroads, rubbing his scruffy chin and gazed up at the snows upon the mountain pass of Arishikage. The ice gleamed like a crown of stars against slabs of coal black rock. Below in the village, spring winds sent the lotus blossoms coursing through the air amid the curling smoke of cook fires.

He glanced high up the pass and it seemed for a moment that dark features moved against the stark white of the snows. But there was no avalanche or rumble. The mountain remained still and silent as death on the frozen peaks.

For a village in springtime, Baiken was also quiet and only the hammering of the blacksmith shop rang in the silence like Buddha’s gong.

The monk went first to the well for a cool drink of water and then approached the blacksmith. He was amused to see it was not an experienced tradesman but a young boy of perhaps seven or eight working the hammer and tongs.

The boy stopped his work and inquired, “Yes? May I help you?”

“I apologize. I didn’t mean to disturb you, but your shop was the only sound I heard in town. So I came here first. You’re perhaps the youngest smith I’ve ever seen.”

The boy sniffed and said, “It is only because my father has been taken away.”

“By the magistrate?”

“No.”

“Local shogunate?”

“No.”

“Bandits?”

“No. Worse.”

“What’s worse than bandits in a valley fair as this?”

“Monsters in the mountain passes, Tengu and Oni. They have laid claim upon our lands and take what they wish in the night. Some say it is a curse put upon us by the sorcerer Yao Hsiang, but I do not know.”

“And of your father?”

“He tried to cross the pass while the monsters slept. He sought assistance from the Daimyo. But we heard his screams. He never made it. Most of the folk here have been taken, were slain, or hide in their hovels.”

“But you still work the forge and hammer.”

“I have naught else to do and I accept my fate. Until it comes, I will do as my father and his fathers have since the day the Yellow Emperor did show men the way of fire and steel. I am a blacksmith.”

The monk rubbed his chin, saying, “It is good you have balance. Is there a home where I may get sustenance?” He rubbed his lean belly.

The boy grimaced. “My mother has some rice and a few onions. Perhaps there is even some Sake. But I would have you earn your meal and work the bellows for me.”

The monk smiled, “You are a good son.”

The boy, Shian-Hu, worked the monk all day and

by evening allowed a respite when they retired to eat. The mother, a taciturn woman, made the meal as her son had promised. They sat by the fire watching the mountain turn purple in the darkness before finally becoming a deeper shade of black against the vaulted night sky.

Here and there upon the mountain were stars just like in the heavens, but these moved across the treacherous snows utterly unlike anything the monk had seen before.

Shian-Hu noticed and commented, “It is the Oni and Tengu. They dance in the passes, likely toying with some poor soul who ventured that way.”

“What more can you tell me about them? Do they have a lord?”

The mother gasped, her first audible utterance since Shian-Hu brought the monk inside their humble home. “It is not meet to speak of such things. It but invites them.”

Shian-Hu shook his head, “If that is our fate, so be it. There is said to be a Demon Lord of the Tengu. But no one alive has confirmed this.”

“Surely some samurai has come to win honor and defeat them?”

“Yes,” nodded Shian-Hu vigorously, “many have. But it is said no weapon forged by man can hurt the Tengu. All of the heroes that went to the mountain have never returned.”

“No weapon forged by man, eh?”

The mother spoke with a biting curt voice, “Monk, you had best return the way you came. There will be only unhappiness in our valley. It is our lot.”

The monk shook his head, “No, in the morning I shall go and speak with these monsters and bid them leave you in peace.”

“And if they will not?” asked Shian-Hu.

His mother stood and shouted down at the ego-less monk. “How can you go where so many mighty men have failed?” To Shian-Hu she said, “We have wasted the last of our rice upon a fool who will only die tomorrow!”

“Mother! Your manners.”

She went into another room and wept. “Forgive me. But we are a poor cursed people.”

“No forgiveness is necessary,” said the monk. “I will take care of this problem in the morning.” With that he sipped the last of his Sake and rolled over to go to sleep.

Shian-Hu, however, could not sleep. The ego-less monk knew something he had not yet revealed, and obviously he was not disturbed over encountering the murderous monsters. The morning would bring a very interesting turn of events.

The monk slept in, well beyond the rising of the red sun. Shian-Hu’s mother complained under her breath that it was merely cowardice in his laziness. But when the monk stirred she became silent.

He did his morning prayers, stretching and refreshed himself with cool water from the well. He gazed up at the mountain pass and turned to bid farewell to Shian-Hu and his mother.

“I am going with you.”

“If you wish.”

“No! I will not have my son journey with you and your assured death.” She held her arms across Shian-Hu, holding him back.

“Listen to your mother,” said the monk. He turned and walked up the path, never once looking back to see what the boy and his mother did.

It was midday before he reached the high pass where the path disappeared between twin mountain peaks. It was colder here but not so much that the monk concerned himself. The chief danger was the glare of the sun upon the snow and ice, blinding him. He kept a hand over his eyes as he squinted against the dazzling white backdrop.

The wind whipped about him and almost had a malevolent voice, whispering threats. The monk made a gesture of Kujo-kiri with his fingers and the spell of wind ceased.

A gentle crack high above erupted with a shower of thunder. A rockslide raced down toward the path. The monk more agile than he appeared sidestepped and jumped behind a sheltering overhang hardly big enough for a dog. As the rolling stones settled, he came out and looked above. Something intangible stirred.

The monk continued up the pass with a spry and wary step.

He heard them before he saw them. Cackling laughter with either mischievous undertones or deep bass rumbles of stifled laughter. The monsters were more easily seen from the corners of his vision than directly. They enjoyed the terror they believed they inflicted upon men, the blood turning to ice as men let fear rule them.

But the monk continued higher up the trail, never acknowledging the demonic chuckling or malicious taunts.

When the monsters had enough of being ignored they called out, “Is this one both deaf and dumb? Does the insect not feel the doom that is upon him?” It was then that a dozen of the crow-man-like Tengu and a score of the ogreish Oni fully revealed themselves from behind fields of glamour. They cloistered around the monk as if about to attack and feed upon his flesh.

Paying them no mind, the monk said, “I would speak with your lord for I have a message for his ears alone.”

This caused alarm and concern among the monsters, for what man would dare presume to have a message for their demonic lord? A towering Oni roared at the monk, sounding like the hurricane and avalanche combined. But the monk yawned. “Do not waste my time any further. Fetch your lord immediately, for I have a message for him.”

The monsters looked to each other and nodded. A black-winged Tengu sprang up and flew into the mist-shrouded clouds near the frozen peak. He returned a short moment later. “Our lord comes and he will feed upon your flesh for your insolence,” spoke the fiend.

The monk said nothing to this, but waited.

The beat of powerful wings, much louder than the other Tengu’s, thumped closer. Where the Oni wore but loincloths and carried hammers and naginatas, the Tengu wore robes of fine silk and wielded katanas. The Tengu lord was dressed in even richer apparel. His silken robe bore many devices and patterns of gold and scarlet. His sword handle was wrought with dragon skin and gems, a gold crown perched upon his ebon brow and his beak seemed to quiver with what could only be an insidious and cruel smile. It was hard to tell with a beak.

His voice was like thunder and he said, booming, “A mortal dares to demand my presence? You will be especially tortured unless you speak a truly valuable message.”

“It is, oh lord of the mountain, it is. I ask for you and your servants to depart, never to return,” said the monk.

The Tengu’s eyes of jet bore into the monk before blinking. Laughter erupted from the Tengu lord. “You are the boldest fool I have ever met. And what if I refuse your offer? Then what?”

“It will hurt,” spoke the monk placidly.

The Tengu lord raged, “Slay him!”

But remaining as still as cold stone, the monk raised his hand, “I have insulted your lordship, perhaps we could compose a challenge for us both. So that you might regain your honor.”

Incredulous the Tengu lord shot back, “Me? Regain my honor? I have lost nothing. What challenge would you have for us, fool?”

“A challenge of life and death.”

“You know no weapons forged by man can hurt me.”

“Yes.”

“And still you wish to challenge me?”

“Yes.”

“Very well. Your doom is upon you.”

They rounded on each other, the Tengu lord standing nearly a foot taller than the monk. Quick jabs with sharp talons rained down upon the old monk, which the monk casually blocked. Raging, the Tengu lord attacked all the fiercer, but quick as he was, he could not grasp the monk in his shining talons.

The monk still only blocked the Tengu lord’s attacks.

“Tell me who you are, monk. To be such a skilled opponent I would know your name,” said the Tengu lord.

“Musashi, Miyamoto. I have come seeking the void and to find worthy adversaries. I have found only you.”

The monsters all blinked in surprise at facing the famed sword saint, even without his katana.

Bolstering his own failing courage, the Tengu lord shouted, “Perhaps you are the greatest human warrior alive, but you have no weapon that can harm me.”

“I am the weapon, not forged by man,” said Musashi as his hand shot out and took the Tengu lord’s beak in h

is left hand.

The Tengu’s eyes grew wide with fear, never before had anyone been able to lay their hands upon him. He pulled back but Musashi’s grip tightened, even to the point of placing two fingers into the nostrils. Horror filled the monster’s black soul as he watched Musashi’s right hammer-like fist rise.

The fist came down at the base of the beak and smote it free. Holding the beak in his fist, Musashi said, “You had the choice between blessing and curse. I grant your wish.”

Screaming and in painful shock, the Tengu lord suddenly went silent as Musashi slammed the broken beak into his feather-covered heart. The monstrous lord fell in the snow, his crimson blood staining the whiteness.

Facing the rest of them with his bloody fist, Musashi spoke softly, “Weapons need to be constantly sharpened and used. Sometimes they break.” He cast the beak at their feet. “Who is next?”

The monsters turned and fled, some melting away into the fog and others taking wing and heading south.

The Tengu lord’s body shifted, cracked, and fell apart in the snows as if it were thousands of years old. The beak on the snows turned to dust and blew away on the wind.

Musashi rubbed his scruffy chin and then continued on his journey.

About the author: David J. West was born with an innate love of books and weapons, pursuing a career writing speculative fiction including: controversial historicals-Heroes of the Fallen, weird westerns-Garden of Legion, shadowy terrors-The Dig, swords & skull-crunchery-Whispers of the Goddess, had to follow. He collects truths, swords, the finest art he can afford, and has a library of 6,000 + volumes because he likes the smell of old books. You can visit him at david-j-west.blogspot.com

Don’t Bite My Finger

Geoff Nelder

Monk Punk and Shadow of the Unknown Omnibus

Monk Punk and Shadow of the Unknown Omnibus