- Home

- Aaron French

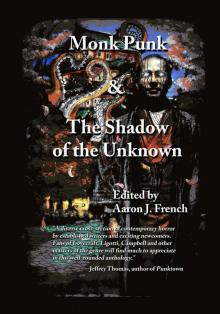

Monk Punk and Shadow of the Unknown Omnibus

Monk Punk and Shadow of the Unknown Omnibus Read online

Praise for The Shadow of the Unknown

"Anyone who tries to breathe new life into the Elder Gods takes an unspeakable risk. But these authors succeed in bringing the darkness home... where it belongs." -- Gary Fry, author of Abolisher of Roses

"The Shadow of the Unknown embraces a leitmotif used by other collections. Yet the volume is not merely another variation on a well-worn theme. The general high quality of the tales redeems the theme's replay and rewards the reader." -- Hellnotes

"An inspired collection." -- Morpheus Tales

"The Shadow of the Unknown is a solid collection of Lovecraftian terrors. It has a nice wide range of styles and settings, with far more hits than misses, and a few real gems gleaming brightly to catch the eye. Fans of the Cthulhu Mythos and weird fiction should give this one a read. Consider it well recommended." -- Horror World

Praise for Monk Punk

"Monk Punk is a great set of stories, each one with something different and unique to offer, and it's an essential for any fantasy fan who loves martial arts." -- Hellnotes

"A fun book to read; a lively, playful collection." -- The Future Fire

"A riveting benchmark in genre fiction and an anthology to be proud of." -- Morpheus Tales

"I enjoyed all of the tales presented here. I wouldn't hesitate recommending any of them." -- Ginger Nuts of Horror

Monk Punk

Omnibus Edition

The Shadow of

the Unknown

Edited by Aaron J. French

ISBN-13: 978-0692275696

ISBN-10: 069227569X

Published by Hazardous Press

Copyright 2014 by Hazardous Press

Cover Art Copyright 2014 by Luke Spooner

This is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, organizations or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

Table of Contents

FOREWORD to the New Edition

Monk Punk

THE SPIRITUAL RIFF, by D. Harlan Wilson

Fistful of Tengu, by David J. West

Don’t Bite My Finger, by Geoff Nelder

The Power of Gods, by Sean T.M. Stiennon

The Key to Happiness, by R.B. Payne

Wonder and Glory, by Adrian Chamberlin

The Just One, by William Meikle

The Liturgy of the Hours, by Dean M. Drinkel

Brethren of Fire, by Zach Black

The Second Coming, by Joe Jablonski

Nasrudin: Desert Sufi, by Barry Rosenberg

Suitcase Nuke, by Sean Monaghan

The Last Monk, by George Ivanoff

The Cult of Adam, by Mark Iles

Snowfall, by J.C. Andrijeski

Xenocyte: A Kiomarra Story, by Caleb Heath

Vortex, by Joshua Ramey-Renk

The Birth of God, by Jeffrey Sorensen

Rannoch Abbey and the Night Visitor, by Dave Fragments

Citipati, by Suzanne Robb

Black Rose, by Robert Harkess

The Path of Li Xi, by Aaron J. French

Where the White Lotus Grows, by John R. Fultz

Monk Punk v. 2.0

Special Bonus Features

Evil Fruit, by Josh Reynolds

Weaned on Blood, by Richard Gavin

Visionaire, by Stephen Mark Rainey

The Perplexed Eye of a Sufi Pirate, by Geoff Nelder

The Bountiful Essence of the Empty Hand, by John R. Fultz

The White Lotus Society, by Aaron J. French

The Shadow of the Unknown

FOREWORD

It Tears Away, by Michael Bailey

Graffiti Sonata, by Gene O'Neill

Blumenkrank, by Erik T. Johnson

To Unsee a Thing, by Richard Marsden

Memories of Inhuman Nature, by Rick McQuiston

What's in a Shell?, by Nathalie Boisard-Beudin

When Clown Face Speaks, by Aaron J. French

The Music of Bleak Entrainment, by Gary A. Braunbeck

The Chitter Chatter of Little Feet, by Fel Kian

Watch for Steve, by Ricky Massengale

Uncle Rick, by M. Shaw

Caverns of Blood, by P.S. Gifford

JP and the Nightgaunt, by Robert Tangiers

Sister Guinevere, by T. Patrick Rooney

Alone in the Cataloochee Valley, by Lee Clarke Zumpe

Quietus, by A.A. Garrison

Amends for an Earlier Summer, by Geoffrey H. Goodwin

Sanctuary of the Damned, by Cynthia D. Witherspoon

The Festering, by James S. Dorr

The Rose Garden, by James Ward Kirk

In the Valley of the Things, by L.E. Badillo

The Devil's Kneading Trough, by Sean T. Page

The City of Death, by Jason D. Brawn

Terror Within the Walls, by K.G. McAbee

The Laramie Tunnel, by R.B. Payne

Amundsen's Last Run, by Nathalie Boisard-Beudin

Antarktos Unbound, by Glynn Barrass

Azathoth Awakening, by Ran Cartwright

The Shadow of the Unknown v. 2.0

Special Bonus Features

The Courtier, by Mike Lester

The First and Last Performance of Varack, by John Claude Smith

Back Acres, by Jay Wilburn

In Silence, by K. Trap Jones

Asleep with the Black Goat, by Aaron J. French

FOREWORD

to the New Edition

Dear Fans and Readers,

When I decided to edit Monk Punk and The Shadow of the Unknown several years ago, my intention was to try and do something completely unique and different, even though I was working with an infinitesimal budget and within the confines of a micro-press. I found the process of compiling these anthologies a lot of fun, and I was pleasantly surprised with the results, as were a number of readers and reviewers.

The authors I worked with, even the bigger names, were accommodating and friendly, and I established wonderful friendships that have continued into the present. These two books served as my editorial training ground, and the most recent release of the projected third in this trilogy of the unusual, Songs of the Satyrs, out now from Angelic Knight Press, closes a chapter in the beginning of my editing career, which also helped pave the way for my current position as Editor-in-Chief at Dark Discoveries.

Recently, when the two anthologies went out of print, I realized they had not reached their full appreciation yet, and that plenty more readers out there might enjoy them. So, when Hazardous Press offered to reprint the books, I proposed the Omnibus concept and began to re-acquire all the rights and track down the authors. The publisher also came up with the idea of including new stories to help warrant purchasing the book by those who had already picked up the originals. We were initially thinking a handful of stories, but this turned into so much more.

The Omnibus Exclusive material featured in the book is fantastic and could constitute a new anthology in and of itself. With stories from Richard Gavin, Stephen Mark Rainey, Josh Reynolds, and others, this is a splendid array of new weird fiction. While typical editorial ethics would warn against including an editor’s own fiction in the book he or she edits, I opted against this rule under the present circumstances, not because I have trouble placing stories, but because I wanted to give readers who picked up the original copies even more content. Thus, I included two new stories of my own—in addition to the original two that had appeared—for a total of four stories by yours truly. So, if you are a fan of my fiction, this is good news for you. If you are not, well…

Another thing: some of these stories are reprints, and yet I have decided not to compile a comprehensive lis

t of acknowledgements, largely in order to meet a self-imposed deadline. This is a gigantic book, and a lot of time and energy went into it. Suffice it to say several of the stories herein have appeared in Dark Discoveries, The End, The Revelations of Zang, Beware the Dark, Morpheus Tales, House of Horror, Bare Bone, Nightscapes, SNM Magazine, Nil Desperandum, The Innsmouth Free Press, and elsewhere. However, most of the Omnibus Exclusive material is original.

Finally, I want to personally thank everyone who purchased, reviewed, and supported the two anthologies when they first came out. And a huge thanks to all the authors and publishers, as well. We have created something fantastic here—a mega-monolithic tome of fresh Lovecraftian and weird fiction goodness, modeled on monk-themed stories and works of surrealistic anomaly. I hope you enjoy it and will pick up Songs of the Satyrs as this trilogy’s conclusion, and continue to follow me along my editorial journey.

Thank you again—

Aaron J. French

May 2014

Tucson, AZ

Monk Punk

THE SPIRITUAL RIFF...

AN INTRODUCTION TO MONKPUNK

D. Harlan Wilson

Monkpunk.

At first glance, the term allocutes a raw paradox: monks do “good,” punks do “bad,” at least according to conventional notions of praxis and morality, sans the drumming of Nietzschean hammers.

According to the OED, a monk is “a man (in early use also, occasionally, a woman) who lives apart from the world and is devoted chiefly to contemplation and the performance of religious duties, living either alone or, more commonly, as a member of a particular religious community.” A punk, in turn, enjoys a wider berth of would-be negative connotations, ranging from the antiquated—a prostitute or gay male concubine—to the contemporary—“a person of no account; a despicable or contemptible person... a petty criminal; a hoodlum, a thug”—the latter of which abandons the stigma of “misplaced” sexuality in favor of uncut transgression and brutality.

The ascetic life of a monk might qualify as transgressive and brutal in itself, if only in its deviation from social norms, its willful introversion, its maintenance of certain ideological values, and its repudiation of basic Darwinian instincts. In the broader spectrum, however, monks mind their own business, whereas punks, by force or will or submission, make other people’s business their own.

Punks violate the body; monks cultivate the mind.

The wingspan of the term comprises two halves of a multivalent binary. Good and evil. Introversion and extroversion. Mental and physical.

Yin and Yang.

Fusing the halves causes a rupture. Signification hemorrhages. One hand infects/inflects the other, and vice versa, and we emerge onto (re)fresh(ed) terrain...

***

In American speculative fiction, punk can be traced back to the Beats, namely William S. Burroughs, who experimented with style, genre and content to the extent that he became a bona fide literary criminal. He became an actual criminal when his novel Naked Lunch was put on trial in the 1960s for obscenity, not to mention when he accidentally shot his wife in the head. Charges were skirted on both counts, but the die had been cast, although punk as a slang term and mode of creativity had not yet come into common usage. It was retroactively associated with Burroughs by artistic “punks” who harnessed the “bad” (i.e., “good”) energy of his vision.

In cut-up form, compliments of Wiki Central for the terminally blipped reader... 1974-76: Ramones, Sex Pistols, Clash... emergent subculture... cosmos of mohawks, stiff and glinting against the stunned firmament... drugs... angry arty collision of styles history vocals squelched high notes discord of electric guitar strings etc... 1983: Bruce Bethke’s “Cyberpunk”... 1984: William Gibson’s Neuromancer—original version ode to Burroughsian scat—edited heavily to satisfy market demands but still monstrously innovative... electronically technologized masculinity... glorification of sci-fi degradation... hypercapitalizm hyperreality hyperspatial matrices of desire and embodiment... 1986: Bruce Sterling’s Mirrorshades: A Cyberpunk Anthology... DISSEMINATION... CULTURAL LEAKAGE... 1986: Splatterpunk—horror riff on cyberpunk... 1987: Steampunk—Victorian riff on cyberpunk... science fictionalization of reality... 21 C.: Postcyberpunk... Post-Everything...

And now: Monkpunk—the spiritual riff...

Of course, my version is somewhat revisionist. Meaning claws for the future but inevitably spirals toward the molting caboose.

***

Genre splicing has become commonplace in recent years as writers and other artists aspire to, in the words of Ezra Pound, “make it new.”

It hasn’t always been this way.

In some circles, the conflation of genres remains sacrilegious. This is especially the case with the principal speculative genres of science fiction, horror and fantasy, whose more conservative devotees romanticize and yearn for an era of clean-cut categorization and fervent rule-following. The postmodern turn scares them. The increasingly mediatized schizophrenization of culture worries them. The fragmented self destabilizes them. But we can’t escape the self, and we can’t escape the cultural machinery that unceasingly produces it. We are the ones who make our maker, after all. We construct what we desire. Even if it kills us.

Whatever the apprehensions of some readerships, the dominant literary punk movements garnered passionate cult followings, partly because of their genre insurrections, but mainly because of the usual suspects: strong prose, dynamic narrative, compelling characters—exceptional writing. Cyberpunk, in fact, reinvented the science fiction genre. Unlike horror and fantasy, this had a lot to do with the themes of cyberpunk—bodily prostheses, cloning, cosmetic surgery, cyberspace, technophilia, etc.—actualizing in various forms in the real world; mainstream authors had no choice but to extrapolate them, or at least demonstrate an awareness of them, particularly if we understand that science fiction is more about the present than an imagined future or a technologically rendered past.

Authorial intent aside, science fiction comments on the sociocultural condition of a given author’s present time, regardless of where the author sets his or her story, and regardless of the degree to which readers are cognitively estranged. Stanley Kubrick’s film adaptation (1971) of Anthony Burgess’s novel A Clockwork Orange (1962) immediately comes to mind. It’s set in an unknown yet not-too-distant dystopian future, but as everything from the film’s sense of fashion to its political and ideological stance tells us, it’s really about the 1960s.

Bruce Sterling has said that “[c]yberpunk comes from the realm where the computer hacker and the rocker overlap, a cultural Petri dish where writing gene lines splice” (xiii). Writers also engaged a noir aesthetic, casting their protagonists as wayward urban cowboys forced to negotiate dark and aggressive technoscapes as much as their own pathological psyches.

Steampunk followed closely on cyberpunk’s heels, even if it had been established long ago, as evinced in, say, Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court (1889). But the term itself is indebted to cyberpunk, and it was the movement’s two figureheads, William Gibson and Bruce Sterling, who incited this additional, retroreconstructive strain in their novel The Difference Engine (1990). Steampunk hurtles backwards to the 19 century, often an alternate version of Victorian England, and favors superstylized mechanical and locomotive technologies over cybernetics.

In good faith, steampunk protagonists often maintain their penchant for assholery.

According to Steffan Hantke, “the shaping force behind steampunk is not history but the will of its author to establish and then violate a set of ontological ground rules” (248). Like cyberpunk, the intricate fusion of multigeneric elements facilitates such a violation.

After steampunk, there was splatterpunk, enfant terrible of the horror genre, and a reaction to the intellectualism of its antecedents. In contrast to the literary punks of the science fiction variety, this subcategory, which came to prominence in the early 1990s, was not distinguished by genre splicing so mu

ch as genre extremism.

The technologies of cyber and steam gave way to a methodology of gore.

As Ken Tucker explains in a 1991 New York Times article, “From H. P. Lovecraft to Stephen King, modern horror fiction has been concerned with the scariness of the unseen—of evil spirits and the rustling sound in the back of a dark closet, of ghostly moans and overactive imaginations. Over the last few years, however, there has been a significant shift in horror fiction; the genre’s traditional jolt of fright now is provided by acts of violence described in elaborate, gruesome detail” (BR13). This movement, too, involved the commingling of different forms. “Splatterpunk is a mocking echo of cyberpunk, the label applied to science fiction’s hard-boiled, high-tech underground movement a decade ago; it is also a conflation of splatter films (the slang term for excessively violent movies like the Friday the 13th and Nightmare on Elm Street series) and punk rock (the willfully crude pop-music revolution sparked in the late 1970s)” (BR13). Practitioners like Edward Lee, Poppy Z. Brite, John Skipp, Jack Ketchum and Clive Barker initiated the movement, which has reemerged in the twenty-first century in the postsplatter cinema of the Saw (2004-09) and Hostel (2005-11) series.

In the wake of the martial punk subgenres, others bloomed. Or, more accurately, exploded. Among them: atompunk, avantpunk, biopunk, clockpunk, elfpunk, mythpunk, nanopunk, nazipunk, nowpunk, postcyberpunk, spacepunk, stonepunk... Most of these offshoots employ some kind of “gonzo-historical” or “anachro-futuristic” aesthetic and “stagnate around a specific technology—bronze, steam, diesel—which then becomes the major contributing factor to the advancement of humankind” (Remy).

Monkpunk is the latest, newest trajectory in the evolving foray of Beat literature. It harnesses the energy and the logos of its forerunners. And it carves out a singular line of flight.

Monk Punk and Shadow of the Unknown Omnibus

Monk Punk and Shadow of the Unknown Omnibus